On July 19th around 6 pm, transportation advocate and experienced cyclist, Charlie Hawkins, was fatally struck while walking his bike across a four-lane road in Warwick, Rhode Island.

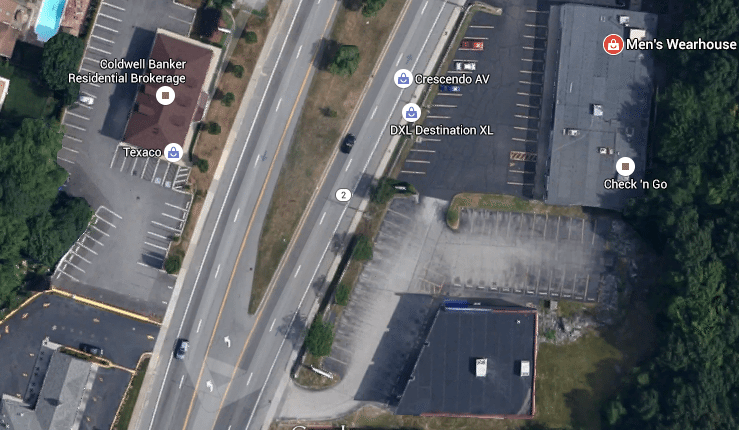

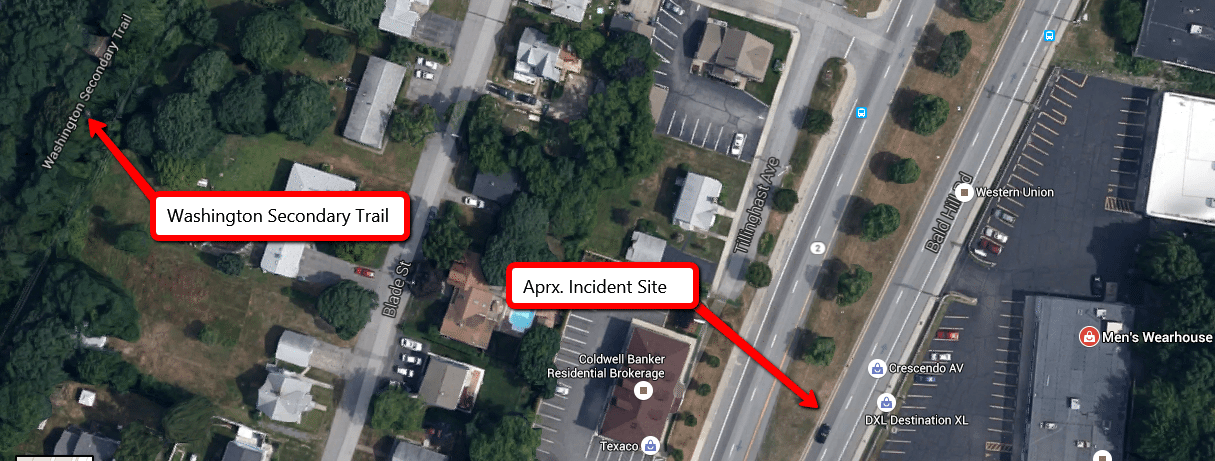

The handful of local reports that surfaced provided little detail about the incident so Traffic Safety Store contacted Alex Krogh-Grabbe, Programs Director for the Rhode Island Bicycle Coalition, to learn about what might have gone wrong. Immediately, Krogh-Grabbe begins dissecting an aerial view of the location where the incident took place:

“The street obviously was not designed for someone to bike on,” he says. “Which is why he had to dismount, which is a bad sign to begin with. He was hit because the street was unsafe for him to be on.”

The road is missing marked bike lanes, crosswalks, and other ‘complete street’ elements, Krogh-Grabbe points out. These components — which can include traffic calming elements such as bump-outs or roadside foliage — make roads safer and more accessible for all users. The site also hosts a commercial strip and Washington Secondary Trail, the largest off-road bike trail in the state, is just yards away, compounding the need for safety.

By contrast, media reports addressed whether the driver was sober, if Hawkins was wearing a helmet, and whether the cyclist should be considered a pedestrian since he was walking his bike. They never discussed street design.

“I’ve heard a few people talk about this crash saying [Hawkins] made some questionable decisions,” Krogh-Grabbe says. “It’s always unfair to lay the blame for traffic violence on the victim.”

Krogh-Grabbe sites three parties who share responsibility in a crash: The person operating the more dangerous vehicle, the designers and engineers who dictate the road’s feature, and the public officials charged with fostering ‘a culture where everyone’s safety is respected.’ Vulnerable road users don’t make the list.

Krogh-Grabbe is an advocate for Vision Zero, a Swedish traffic philosophy where vehicular fatalities are deemed unacceptable. The concept allows for human error — engineers, planners, and policymakers are also held accountable.

Vision Zero has helped Sweden cut traffic fatalities to 25% the U.S rate. It’s taken hold in New York, San Francisco, and other large U.S. cities, and on March 2015, The Federal Highway Administration adopted Vision Zero as a guiding approach. Still, Krogh-Grabbe, who says he’s been actively pushing for Vision Zero for his state, believes much of the country is behind.

“[Vision Zero] has been sweeping through American cities,” he says. “I’d love to see more communities adopt this target. Every time you see someone hit by a vehicle and killed or seriously injured, it makes you wonder, ‘why are we designing our streets this way?'”

Krogh-Grabbe admits Vision Zero will be hard work. It requires significant resources for evaluating street designs and measuring results. Additionally, Vision Zero asks officials to engage and collaborate with everyday street users. That’s something, Krogh-Grabbe believes, we should already be doing. He pauses and brings up another recent incident: Ani Emdjian, a nine-year-old girl was fatally struck this past spring while crossing the street in Providence, RI.

“It’s not just a niche issue,” he says. “These are people. Honestly, any other goal is unethical.”

Top Image: Paul Krueger on Flickr